17 Black Women to Honor During Black August

First, What is Black August?

Black August was started in 1970s California by incarcerated Black freedom fighters. Its goal is to honor the lives and deaths of Black political prisoners killed by state-sanctioned violence, bring awareness to prison conditions and current political prisoners, and honor the tradition of radical Black resistance against anti-Black violence and systemic oppression. BLACK AUGUST - M4BL

While Black August centers Black political prisoners, the idea of who is and isn’t a political prisoner becomes less important in the face of the interconnected violence of the prison system and the state itself. Anyone whose experience and existence is threatened by targeted violence remains a prisoner of fear.

Black August also contends that those involved in the fight for Black liberation continue to draw inspiration and strength from their predecessors. Historian Herbert Aptheker quotes the remark of one New African involved in the civil rights movement of the 1970s:

From personal experience I can testify that [...] slave revolts made a tremendous impact on those of us in the civil rights and Black Liberation movement. It was the single most effective antidote to the poisonous ideals that Blacks had not a history of struggle or that such struggle took the form of non-violent protest. Understanding people like Denmark Vesey, Nat Turner, William Lloyd Garrison etc. provided us with that link to our past that few ever thought existed.

Though this sentiment continues to inform the ideals of Black August, activists like maya finoh emphasize the importance of inclusivity in the concept of freedom.

When Black organizers center the leadership of hyper-marginalized Black people — Black women, disabled, poor, incarcerated, queer, trans, and nonbinary people — and demand a new kind of Black radical unity, we are honoring the Black August tradition of orienting ourselves toward the total liberation and self-determination of all Black people.

Read maya finoh’s article, Black August Celebrates the History of Black Resistance in the U.S. to learn more. And without further ado….

17 Freedom-Fighting Black Women You Should Know About!

Anna Julia Cooper

Washington, D.C.

“I care not for the theoretical symmetry and impregnable logic of your moral code; I care not for the hoary respectability and traditional mysticisms of your theological institutions; I care not for the beauty and solemnity of your rituals and religious ceremonies; I care not even for the reasonableness and unimpeachable fairness of your social ethics—if it does not turn out better, nobler, truer, men and women—if it does not add to the world's stock of valuable souls—if it does not give us a sounder, healthier, more reliable product from this great factory of men—I will have none of it.”

—Anna Julia Cooper

Anna Julia Cooper was an author, teacher, sociologist, and Black liberation activist. Born into enslavement in August 1858, she went on to study at Oberlin college, where she received her BA in 1884, and her master’s degree in mathematics in 1887. After her graduation, Cooper worked at Wilberforce University and Saint Augustine’s before moving to Washington, D.C. to teach at Washington Colored High School.

By 1892 Cooper had published her first book, A Voice From the South by a Black Woman of the South. The book called for equal education for women and emphasized that educating Black women was essential for advancing the rights of Black people as a whole.

Cooper also founded many organizations promoting Black civil rights causes. She helped start the Colored Women’s League in 1892, was on the executive committee of the first Pan-African Conference in 1900, and created inclusive branches of the Young Women’s Christian Association and the Young Men’s Christian Association in Washington, D.C.

In 1911 Cooper once again resumed her graduate studies, this time at Columbia University in New York City. But just four years later, following the death of her brother, she put her education on pause to raise five grandchildren. A year after resuming her studies in 1924 at the University of Paris in France, Anna Julia Cooper became the fourth Black woman in the world to receive a doctorate degree. She was 67 years old when she received her doctorate of philosophy. Cooper taught until 1930 when she assumed the presidency of Frelinghuysen University, a school for Black adults. After the school was reorganized into into the Frelinghuysen Group of Schools for Colored People, she worked as the school’s registrar until its closure in 1950.

Sonia Sanchez

New York, New York

“All poets, all writers, are political. They either maintain the status quo, or they say, ‘Something’s wrong, let’s change it for the better.’”

—Sonia Sanchez

Writing is a personal and political act for Sonia Sanchez. She rose as a formative figure in the 1960s Black Arts Movement, using her voice in the name of civil rights, women's liberation, Black culture, and peace. A poet, playwright, educator, and activist, she was one of the first people to utilize the power of spoken word.

Sanchez was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1934. After her mother’s death when Sanchez was only one year old, she went to live with relatives nearby. By 1943 she and her sister had moved to Harlem, NY to live with their father.

In 1955, Sanchez attended Hunter College and earned a BA in political science before doing postgraduate work at New York University and studying poetry with Louise Bogan. She then founded a writer’s workshop in Greenwich Village, whose members included notable poets like Amiri Baraka, Haki R. Madhubuti, and Larry Neal. Sanchez then went on to form the “Broadside Quartet” alongside Etheridge Knight, Madhubati, and Nikki Giovanni.

In the early 1960s, Sanchez supported the integrationist philosophy of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), but after considering the ideas brought forth by Malcom X, she began to focus on her Black heritage in regard to Black liberation worldwide.

Sanchez began teaching in the California Bay Area in 1965 and was key in developing Black studies courses at San Francisco State University. She also taught at Temple University, where she was named the first presidential fellow.

In the words of Joy Harjo, “Her songs of destruction and loss scrape the heart; her praise songs thunder and revitalize. We need these songs for our journey together into the next century.”

The many prizes Sonia Sanchez has received include the Robert Creeley Award, the Frost Medal, the Community Service Award from the National Black Caucus of State Legislators, the Lucretia Mott Award, the Outstanding Arts Award from the Pennsylvania Coalition of 100 Black Women, the Peace and Freedom Award from Women International League for Peace and Freedom, the Pennsylvania Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Humanities, a National Endowment for the Arts Award, a Pew Fellowship in the Arts, and the Wallace Stevens Award, given each year to those with outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry.

Read more about Sonia Sanchez in the article below from our friends at Black Women Radicals ⬇️

Exploring the Transformative Poetry of Sonia Sanchez

You can also visit Sonia Sanchez’s official website here.

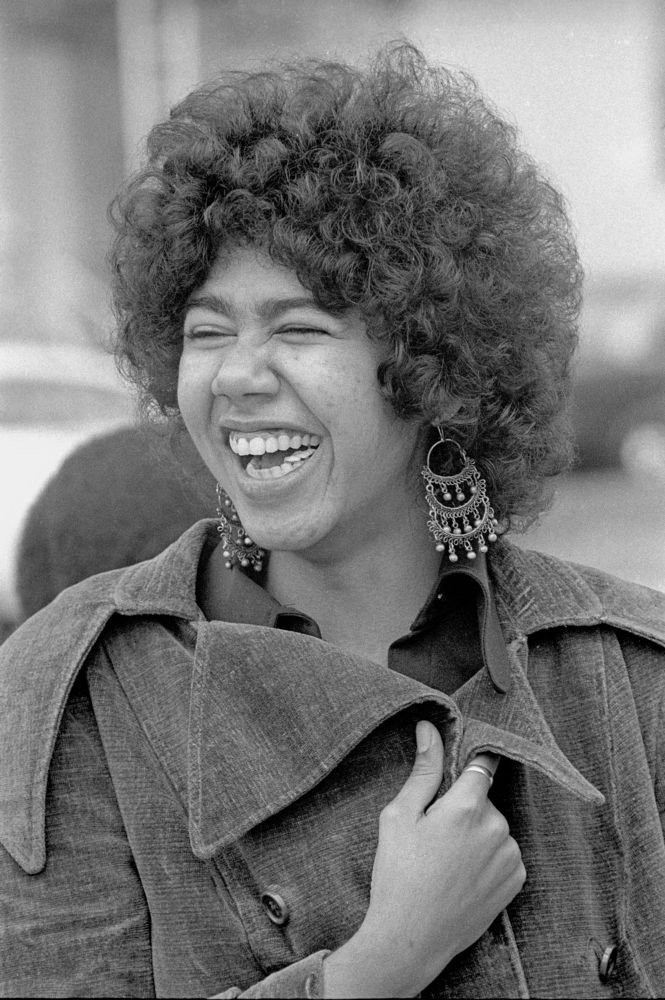

Angela Davis

Los Angeles, California

“Feminism involves so much more than gender equality and it involves so much more than gender. Feminism must involve consciousness of capitalism (I mean the feminism that I relate to, and there are multiple feminisms, right?). So it has to involve a consciousness of capitalism and racism and colonialism and post-colonialities, and ability and more genders than we can even imagine and more sexualities than we ever thought we could name.”

—Angela Davis

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Angela Davis grew up in a neighborhood nicknamed “Dynamite Hill” due to the regular Ku Klux Klan bombings targeted at Black families in the area. In her teen years, Davis coordinated interracial study groups which were disrupted by the police. Though she moved away from Alabama, she knew girls that were killed in the Birmingham church bombing of 1963.

Davis studied philosophy with Herbert Marcuse at Brandeis University and received her graduate degree from the University of California (UC), San Diego before going on to teach at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and UC Santa Cruz. During this time she worked with the Black Panthers and the Che-Lumumba Club, a Black branch of the Communist Party. Davis was also a strong supporter of the Soledad brothers, including George Jackson, whose works became an important reference for Black August (his death prompted organizers to fast, wear commemorative black armbands, and eventually carry out the Attica Prison Uprising in 1971). At Jackson’s trial in 1970, an escape attempt using guns registered in Davis’ name left her facing charges including murder, for which she landed on the FBI’s Most Wanted list and spent 18 months in jail. While Davis remained in prison, people worldwide took up the campaign to “Free Angela Davis,” and formed the Angela Davis Legal Defense Committee. In her honor, John Lennon and Yoko Ono wrote “Angela” and the Rolling Stones wrote “Sweet Black Angel.”

Finally, she was acquitted in 1972.

Davis retired in 2008 but continues to lecture at various universities, and in 2017 she was a featured speaker and honorary co-chair at the Women’s March on Washington following Donald Trump’s inauguration. Davis authored several books including Angela Davis: An Autobiography (1974), Women, Race and Class (1980), Women, Culture and Politics (1989), Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday (1999), Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003), Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and Torture (2005), The Meaning of Freedom (2012), and Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement (2016).

Joan Little

Washington, North carolina

“Every hurt and pain I feel inside,

Every time I pick up the morning news

only to see my name on the front page –

I begin to wonder; they make me feel

less than somebody.”—Joan Little, I Am Somebody

In 1974 Joan Little was sexually assaulted by a prison guard at Beaufort County Jail. She defended herself by stabbing her assaulter, only to be charged with first-degree murder. Little’s case led to global outcry and protest, and after a 5-week trial, she was acquitted. It was the first time in history a woman was acquitted on the grounds of self-defense against sexual assault.

To learn about ongoing campaigns for freedom of victims of sexual assault visit Survived & Punished.

Delores Henderson, Joyce Lee, Mary Ann Carlton, Joyce Means, and Paula Hill

Oakland, California

This photo of Delores Henderson, Joyce Lee, Mary Ann Carlton, Joyce Means, and Paula Hill was taken at the ‘Free Huey!’ rally in Oakland, CA. These five women were known as some of the “rank and file” members of the Black Panther Party, because while their names didn’t often make headlines, they did important work maintaining the daily operation of the party, sometimes working 17, 18, or 19-hour days. They rallied, handled administrative duties, executed public-facing strategy, worked as armed security or organizers, and helped coordinate design, production, and distribution of The Black Panther newspaper. They also helped run panther-founded community service programs.

Of the Black Panthers, Henderson told Smithsonian Mag,

“I liked what they said. I wasn’t having good feelings with white people in Sacramento. I was eight or nine when we moved there from Portland, Oregon, and as soon as I started school, I was being called a black ghost,” she remembers, along with other racial epithets. “People said, ‘don’t let them call you that,’ so I was fighting almost every day, getting into trouble. When I got older, I realized that Sacramento—and I’ll say it to this day—is the most prejudiced place I have ever been. It was absolutely horrible.”

Elaine Brown

Los Angeles, California

“We were the women in the Black Panther Party, and we were sisters and we were strapped and we fought back just like any man… Too many of [the male leadership] seemed satisfied to appropriate themselves for the power the party was gaining, measured by the shiny illusion of cars and clothes and guns.”

—Elaine Brown

Born in 1943 in North Philadelphia, Elaine Brown was the only woman to ever lead the Black Panther Party. Though she was raised by a single mother and experienced economic hardship, she was able to attend private school and participate in extracurricular activities such as ballet and classical piano. Brown attended Temple University before deciding to pursue music in Los Angeles and enrolling in UCLA instead. There, she became involved with music executive Jay Richard Kennedy, who buoyed her interest in social justice movements.

Soon after, Brown began working for the Black newspaper Harambee and attending Black Panther meetings. As a member, she helped create the first Free Breakfast for Children program, Free Busing to Prisons program, and Free Legal Aid program in Los Angeles. She went on to become the South California Branch editor of The Black Panther, replace Eldridge Cleaver as Central Committee Minister of Information, and record songs for the album Until We’re Free with party Founder and Minister of Defense, Huey P. Newton.

Brown was chosen by Newton to take over in 1974 when he moved to Cuba to dodge criminal charges, and she led the party through 1977. While chairwoman, she directed Lionel Wilson’s political campaign to victory, and Wilson became Oakland’s first Black mayor.

In 1978, she left her position after growing disgusted with the derogatory party attitudes towards women, evidenced by Huey Newton’s command that a woman member be beaten following his return to the United States. Brown then moved back to Los Angeles to raise her daughter.

Later in life, Brown continued to fight for radical prison reform and education for Black children living in poverty. She briefly declared a candidacy for the Green Party in the 2008 presidential election, but ultimately left because she felt that the white people who made up the majority of the party would not take steps enacting real change. Brown now gives lectures on prison reform at various conferences and universities.

Ericka Huggins

Los Angeles, California

“While awaiting trial for two years before charges were dropped, including time in solitary confinement, I taught myself to meditate as a means to survive incarceration and separation from my baby daughter. From that time I’ve incorporated spiritual practice into my community work, as a speaker and facilitator, teaching as a tool for change - not only for myself, but for all people, no matter their age, race, gender, sexuality or culture.”

—Ericka Huggins

Born in 1948, Ericka Huggins states that her desire to serve humanity was sparked at 13 years old in her hometown of Washington, D.C. when she attended the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Five years later, at 18 years old, she joined the Black Panther Party. She then went on to become a leader of the Los Angeles party chapter and eventually, the New Haven, Connecticut, chapter alongside her husband John Huggins. She led these chapters for a total of fourteen years. In 1969 she was arrested in New Haven for conspiracy charges alongside Bobby Seale, and their political imprisonment led to “Free Bobby, Free Ericka” rallies nationwide.

Two years later, when her charges were dropped, Huggins became Director of the Oakland Community School. She was the first woman as well as the first Black person to be appointed to the Alameda County Board of Education. Later, she went on to teach Women and Gender Studies at San Francisco State University and California State University, East Bay, as well as Sociology and African American Studies in the Peralta Community College District. She was also the first woman practical support volunteer coordinator for the Shanti Project during the HIV/AIDs crisis in the 1990s.

Huggins is now a facilitator of World Trust, an organization that uses films to document the impact of systems of racial equality.

You can learn more by visiting Ericka Huggins’ official website here.

Kathleen Cleaver

San Francisco, California

“We are born with our hair like this and we wear it like this. It’s natural. Because, the reason for it, you might say, is like a new awareness among Black people that their own natural appearance, physical appearance, is beautiful.”

— Kathleen Neal Cleaver

Born in Dallas, Texas, in 1945, Kathleen Cleaver was an influential figure in the Black Panther Party. Her activism began when she left Barnard College to join the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). She organized a student conference at Fisk University where she met her future husband Eldridge Cleaver, Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party. Together they moved to San Francisco where she became Communications Secretary, making her the first woman in Party leadership.

Despite the fact that over two thirds of Black Panthers members were women, Cleaver was one of few to hold senior positions within the Party. She served as spokesperson and press secretary, organizing demonstrations, creating pamphlets, holding press conferences, designing posters, and speaking at rallies and to the press. Notably, she organized the national campaign to free the Party's incarcerated minister of defense, Huey Newton.

After spending years exile in Algeria and France, Cleaver returned to the U.S. in 1975 to pursue undergraduate and graduate studies at Yale and become a professor of law. Since then she has held multiple professorships and worked as a law clerk in the U.S. Court of Appeals. She is currently a senior lecturer at the Emory University School of Law and continues to be a lifetime activist for racial and gender equality.

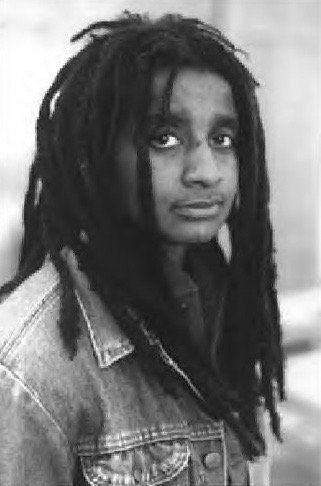

Assata Shakur

“The usual way the people are taught to think in Amerika is that each subject is in a little compartment and has no relation to any other subject. For the most part, we receive fragments of unrelated knowledge, and our education follows no logical format or pattern. It is exactly this kind of education that produces people who don’t have the ability to think for themselves and who are easily manipulated.”

—Assata Shakur

Assata Shakur is a revolutionary Black icon, whose story has led her to become a patron saint of Black rebellion in the last fifty years. Shakur was a target of the FBI’s calculated attempts to criminalize political dissent and oppress activists. Throughout the 1970s, their COINTELPRO surveillance program targeted and assassinated leaders of the Black Liberation Movement using tactics which would later be found illegal by Congress.

Born JoAnne Deborah Byron in 1947 New York City, Shakur spent her youth traveling between homes with her mother in New York and relatives in Wilmington, N.C.

Her exposure to Black Nationalist organizations while studying at City College of New York was one of her main introductions to activism. She attended meetings for the Golden Drums, where she met her husband Louis Chesimard, and learned about historical Black figures that fought against oppression and systemic violence. She also began participating in groups advocating for student rights, anti-Vietnam war, and Black liberation.

In 1971, she took on her new name: Assata (“she who struggles”) Olugbala (“love for the people”) Shakur (“the thankful”).

During a trip to Oakland, California in her 20s, Shakur became acquainted with the Black Panthers and joined the Harlem branch upon her return to New York. There she worked in the breakfast program but eventually became disaffected with the Party due to their reluctance to collaborate with other Black organizations. She then became a member of the Black Liberation Army (BLA), an organization that believed in open resistance.

In 1973, Shakur was pulled over by New Jersey police. Shots were fired and one BLA member and one police officer were killed. Shakur was charged with the murder of the officer and sentenced to life in prison. She spent 6 and a half years incarcerated, delivering her daughter Kakuya Amala Olugbala during this time. The two were able to reunite when Shakur escaped to Cuba in 1984. She was on the FBI’s Most Wanted List up until as recently as 2013, with a 2 million dollar bounty on her head.

Much lore surrounds Shakur due to her forty-year elusion of law enforcement as well as her proximity to hip-hop fame as the step-aunt and godmother to the late Tupac Shakur.

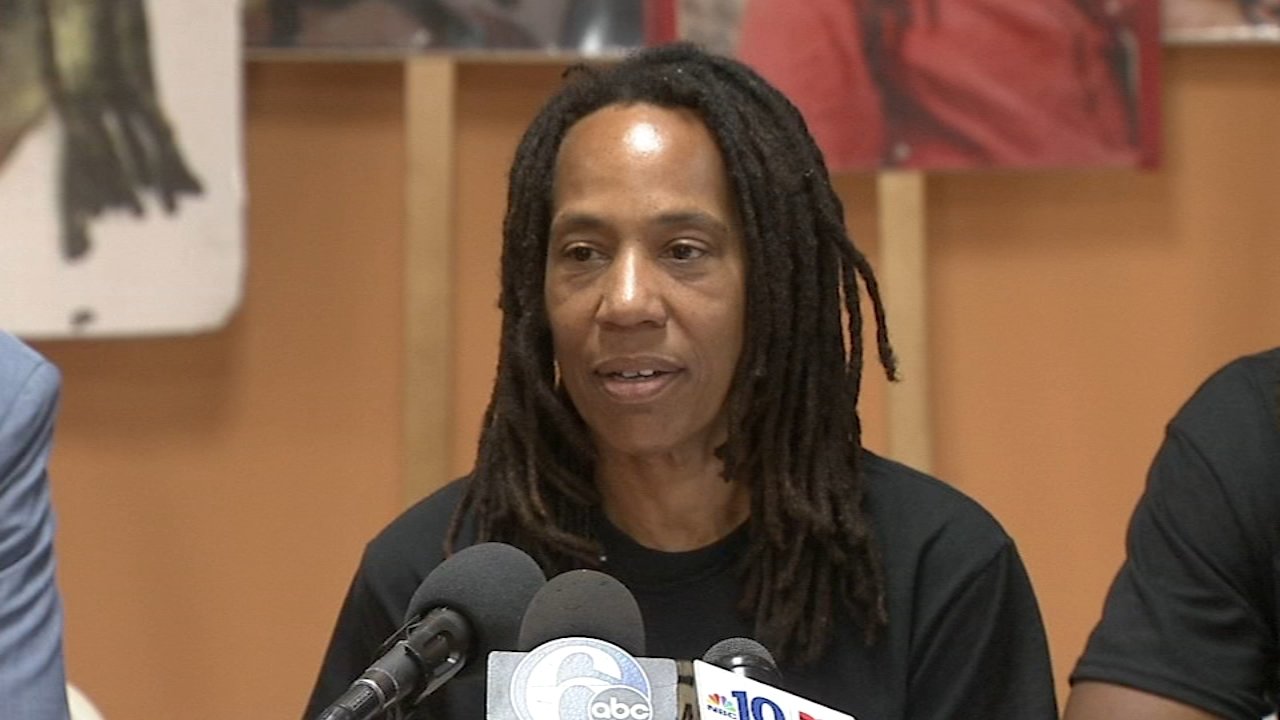

Janine Phillips Africa and Janet Phillips Africa

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

“There are times when I think about Life and my son Phil, but I don’t keep those thoughts in my mind long because they hurt. The murder of my children, my family, will always affect me, but not in a bad way. When I think about what this system has done to me and my family, it makes me even more committed to my belief.” —Janine Phillips Africa

Janine and her sister Janet were both members of the MOVE organization, whose members lived in a communal house, adopted the surname ‘Africa’ in order to become family in writing, cared for stray cats and dogs, and proclaimed Black liberation day and night. Janine and Janet were arrested after an infamous 1978 shootout in which police officer James Ramp was killed. All members of MOVE 9 were charged with the murder, though they maintain their innocence, stating that the single bullet which killed Ramp came from the gun of another officer. Janine’s youngest son Life was killed in the struggle, and her son Little Phillip was killed seven years later by an incendiary bomb which set fire to the MOVE house. Political prisoners for forty years, Janine and Janet were finally granted parole in 2018.

Debbie Sims Africa

Philadelphia, Pennsylania

“It was a hard, hard decision. I wanted what was best for him and I knew that was not to get close to me at any level. So I had to break the bond.” —Debbie Sims Africa on her decision not to connect with her son in his early life.

Eight months pregnant at the time of the 1978 shootout, Debbie Sims Africa was another member of MOVE 9 arrested after James Ramp’s death. She gave birth to her son Mike Africa Jr. a few weeks into her sentence, and with the help of other prisoners, was able to spend three secret days with him before eventually being separated by prison guards. At six years old Mike Jr. learned that both of his parents were incarcerated, and began to visit them one or two times a year. Debbie and Mike Jr. were reunited when she was the first MOVE 9 member to be granted parole after four decades. Mike Jr.’s father was released from prison later in 2018, and he and Debbie were married soon after. The MOVE organization still exists, though differently, today, and Debbie’s family remains committed to the MOVE ideals of peace, social justice, a healthy lifestyle, and environmental protection.

Merle Austin Africa

Philadelphia, Pennsylania

Merle Austin Africa was another one of the women of MOVE 9 to be arrested after the 1978 shootout. She died in prison in 1998 under unclear circumstances, and the MOVE organization holds the system officials who put her in jail responsible for her early death.

Joy Powell

Rochester, NEW York

“Do Black women political prisoners matter too?”

—Joy Powell

Born in 1962, Joy Powell is a community activist and Pentecostal pastor currently imprisoned in New York State.

After allegedly being raped by a correctional officer in 1995 and having the police refuse to investigate her case, Powell began routinely holding local protests and calling for police accountability.

Powell continued to run local charitable events and operated a youth homeless shelter out of a salon she owned. She also began coordinating candlelight vigils for victims of neighborhood gang violence after her son was killed as a bystander to a shooting in 2000. Following the shooting of a mentally ill man in her community, she fought to create an “Emergency Response Team” to handle mental health crises and require officers in the Rochester Police Department to receive additional specialized training.

As an activist against police brutality, violence and oppression, Rev. Joy Powell was warned by the Rochester Police department that speaking out against corruption in her community made her a target, and in 2006, she was accused of 1st Degree Burglary and Assault.

Tried by an all-white jury, the state provided no evidence and no eyewitnesses against Powell. She was not allowed to talk about her activism or discuss the fact that she was a pastor. Unsurprisingly, she was convicted. While serving a 16-year sentence, she was charged with second degree murder in a case from 1992, for which she was convicted and sentenced to 25 years to life.

Powell is currently seeking counsel to file an appeal and continues to advocate from behind bars on behalf of fellow prisoners.

For more herstory-makers follow our sister account: @FEMINIST.HERSTORY

we share powerful stories from the archive daily.

Sources:

M4BL. “BLACK AUGUST.” Accessed August 3, 2022. https://m4bl.org/black-august/.

finoh, maya. “We Should All Be Commemorating Black August.” Teen Vogue, August 10, 2020. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/what-is-black-august.

“Anna Julia Cooper | Columbia Celebrates Black History and Culture.” Accessed August 5, 2022. https://blackhistory.news.columbia.edu/people/anna-julia-cooper.

Poets, Academy of American. “About Sonia Sanchez | Academy of American Poets.” Text. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://poets.org/poet/sonia-sanchez.

Editors, History.com. “Angela Davis.” HISTORY. Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/angela-davis.

National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Angela Davis.” Accessed August 5, 2022. https://nmaahc.si.edu/angela-davis.

Barnard Center for Research on Women. “Joan Little: Survived and Punished,” June 20, 2017. https://bcrw.barnard.edu/videos/joan-little-survived-and-punished/.

“Prison Culture Poem of the Day: ‘I Am Somebody’ by Joan Little.” Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/2014/04/10/poem-of-the-day-i-am-somebody-by-joan-little/.

Magazine, Smithsonian, and Janelle Harris Dixon. “The Rank and File Women of the Black Panther Party and Their Powerful Influence.” Smithsonian Magazine. Accessed August 3, 2022. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/rank-and-file-women-black-panther-party-their-powerful-influence-180971591/.

HuffPost. “Former Black Panther Leader On How The Party’s Enduring Spirit Started A Revolution,” October 14, 2016. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/elaine-brown-black-panther-leader-revolution_n_5800ddabe4b0162c043b61bc.

National Archives. “Elaine Brown (March 2, 1943),” August 25, 2016. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/individuals/elaine-brown.

Ericka Huggins. “Bio | Ericka Huggins Official Website.” Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.erickahuggins.com/bio.

National Archives. “Kathleen Cleaver (May 13, 1945),” August 25, 2016. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/individuals/kathleen-cleaver.

Paula Rogo, Essence. “8 Things to Know About Assata Shakur and the Calls to Bring Her Back from Cuba.” Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.essence.com/culture/assata-shakur-facts-call-return-from-cuba/.

“Assata Olugbala Shakur (1947-),” February 8, 2014. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/assata-olugbala-shakur-1947/.

Pilkington, Ed. “Born in a Cell: The Extraordinary Tale of the Black Liberation Orphan.” The Guardian, July 31, 2018, sec. US news. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/jul/31/debbie-sims-africa-mike-jr-black-liberation-orphan-move-nine-philadelphia.

Pilkington, Ed. “Move 9 Women Freed after 40 Years in Jail over Philadelphia Police Siege.” The Guardian, May 25, 2019, sec. US news. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/may/25/move-9-black-radicals-women-freed-philadelphia.

Tamar Sarai, Essence. “America Is Still Locking People Up for Their Activism, Including Black Women.” Accessed August 5, 2022. https://www.essence.com/news/black-women-political-prisoners/.

"NU Day Resurrection and Liberation". BlogTalkRadio. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

"Support Rev. Joy Powell | Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women". resistancebehindbars.org. Retrieved 2016-12-05.

Free Joy Powell. “Meet Joy.” Accessed August 5, 2022. http://box5341.temp.domains/~freejoyp/?page_id=350.

Thanks to InspiringQuotes, LibQuotes, and AZQuotes.